by Mark Schwartz, Sc.D. and Lori Galperin, LCSW

We are bonding creatures. As we age, our capacity to form deeper connections with others generally increases. In other words, the capacity to love is a developmental achievement. Our survival as children depends on a parents’ capacity to protect us from danger as well as their ability to nurture the development of robust neurological systems that ensure eventual pair-bonding, procreation, and caretaking of infants.

The blueprint for how one loves is “laid-in” within the context of the family. Therefore, if an individual is rarely exposed to verbal or physical affection, they are not provided with this representational model, i.e., the language for loves’ expression. The basic instinct to bond can be counterbalanced with fears of abandonment, punishment, or rejection, which form barriers to later bonding efforts from others. The instinct therefore becomes a ship with neither a rudder nor direction, moving forwards and backwards, closer and farther out, towards and away, partner after partner. The individual oscillates from clingy and needy to avoidant and rejecting.

A question commonly asked of addicts in therapy is, “What are you afraid will happen if you give up your addiction?” The response is usually something along the lines of, “I’ll be alone.” It is as if the behavior fills the emptiness of devoid attachment, temporarily allowing for some relief. Thus, once the individual attains abstinence, there is an opportunity to discover the means to repair the hollowness created by their unmet capacity to connect with others in a meaningful way. Usually, misguided attempts lead to the development of a “false self,” like an actor on stage compulsively meeting other peoples’ needs to prevent rejection or abandonment. Furthermore, a person distracts themselves from thoughts and feelings at the expense of developing real human connection. Even if the individual finds others who are capable of bonding, it is as if there is an inability to receive their love. Most often, however, the individual avoids loving partners and forms destructive relationships with those who are similarly injured. Repair requires the resolution and substitution of these core frameworks and processes.

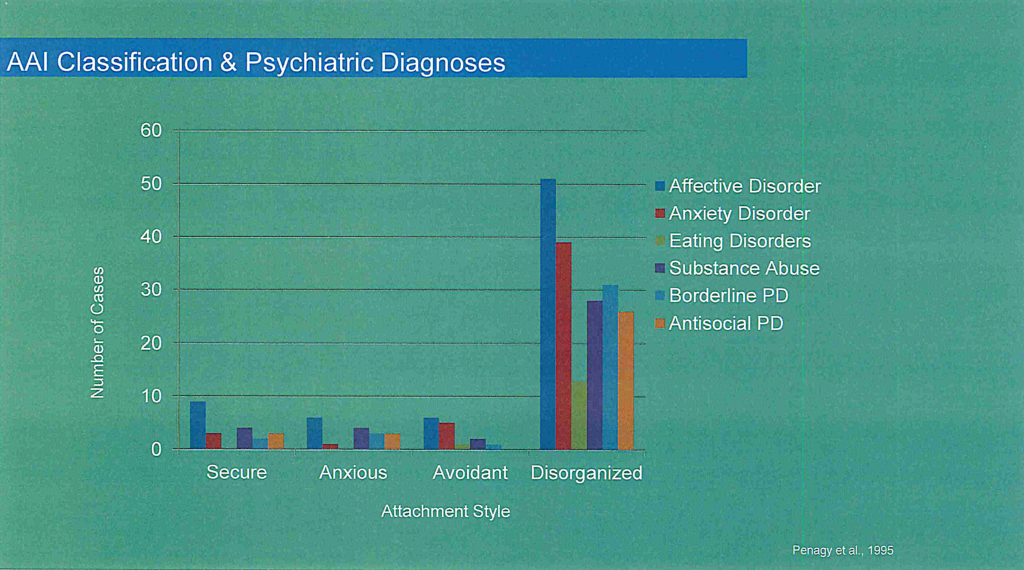

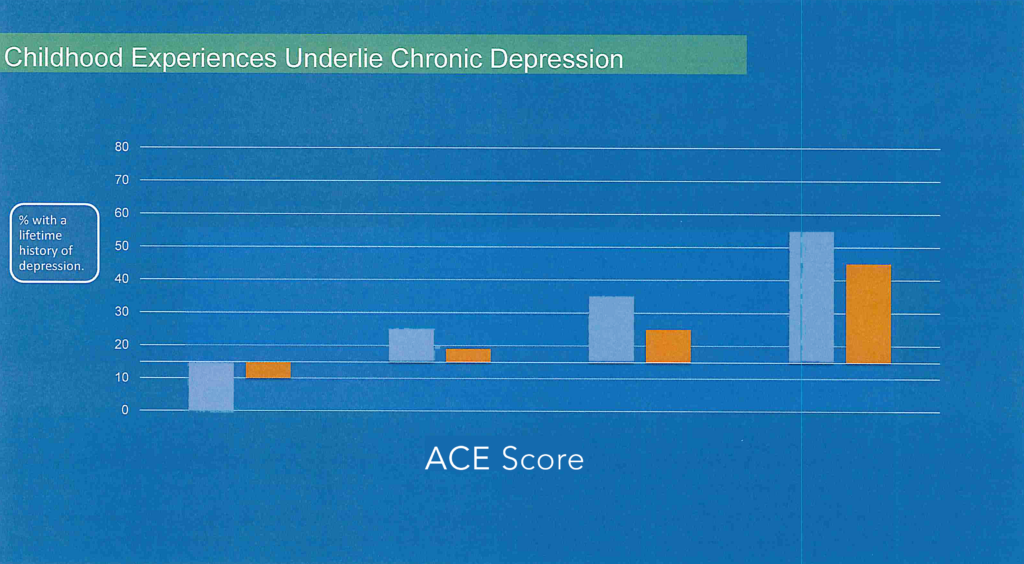

The concept of “intimacy disorder” can be studied empirically within the vast breadth of research related to Disorganized Attachment (DA). This work begins with Bowlby, Ainsworth, and Main and has been followed for 30+ years by Sroufe and many others. DO has been observed in the laboratory between infant and caretaker as early as 18 months of age, where the need to bond has become associated with fear of rejection, abandonment, or punishment. Follow-up research of such an individual suggests that DA predisposes a person to later mental health issues and addictive behavior in adulthood (see Figures 1 and 2, below).

Disorganized Attachment (DA) places the individual at great risk of psychopathology and addictive behavior, evolving from a lack of self-integration, emotion regulation, and capacity for goal directed self-oscillation in select areas of their life. The result is the chronic feeling of anxiety and self-derogation that appears impervious to actual accomplishment or feedback. The individual is unable to turn to themselves or others for any reliable self-soothing or comfort, and instead feels perpetually empty and alone. Individuals attempt to fill this vacuum by reaching for food, sex, gambling, religion, work, alcohol, or drugs, perpetually reaching for more as these bonding alternatives fail to meet the actual need. The individual will present to the clinician with statements such as, “I don’t know who I am,” “I feel like a chameleon,” “I don’t know what my life is about,” much like a leaf blowing in the wind. There is no “I” to form a “we.” What results are cycles of avoidance entwined with the intensive chasing of what one cannot have.

Additionally, there is often an obstructed capacity for emotional recognition, regulation, tolerance, and expression, all of which are essential for an individual to know themselves and read others accurately. The ability to know oneself and read others is what researchers often refer to as “metacognition.” Unmet attachment needs along with the absence of boundaries, structure, and limits within the family of origin result in such obstruction and deficiency of metacognitive ability. One example of deficient metacognition is a person’s preoccupation with pleasing others in order to feel needed, which serves to compensate for an absent sense of self and resulting self-hate.

Alternatively, a person can present with an unmet capacity for empathy or compassion, leaving the individual in a perpetual state of adolescence. Treating and healing disorders of self and affect regulation are the cornerstones of recovery for both addiction and mental health disorders. Nurturing the capacity for intimacy and physical manifestations related to sexuality are requisites for clinicians who do the “deeper” work underlying psychiatric behavioral and relational presentations.

The most useful contemporary psychotherapeutic innovations for repair of DA derive from the work targeting dissociative disorders. In his longitudinal studies of DA, Sroufe recognized that the most frequent adult consequence of DO is a dissociative disorder. Fragmentation of the self-system results in polarizations. For example: the individual who feels incapable while also knowing they are smart; becoming a priest to care for others while molesting children; or becoming over-caring for children to compensate for an extreme resentment of their existence. Fragmentation of the self-system is the cause of the addictive personality and the repetition of self-injurious behavior. It is as if injured parts of self remain at the chronological age of the injury while the individual continues to mature, resulting in one feeling defective while unaware that they are extraordinary.

Therapies that have a Gestalt basis — i.e. structural dissociation — work with disparate parts of self and allow for insight into the origins of fragmentation, while trauma-resolution therapies eventually allow for self-integration — the primary goal of psychotherapy. This is followed by the teaching of critical skills missed in a child’s early development and resulting from insult or injury caused by subsequent rejections and traumas. Relational and sexual skills are often a requisite component of this repertoire.

Further elaboration on these fundamental concepts will be provided in our upcoming LIVECAST WEBINAR on Friday, April 21 at 9:00 a.m. PDT with Dr. Mark Schwartz and Lori Galperin, LCSW as they discuss:

- Disorganized Attachment

- Disorders of Self

- Emotions

- Intimacy

- Pair Bonding

- Sexuality

- Marital Therapy

- Addiction

JOIN US! FREE LIVECAST WEBINAR ON FRI APR 21 | 9:00 – 11:00 a.m. PDT, “Intimacy and Intimacy Disorders: The Cornerstone of Recovery from Mental Illness and Addiction”

REGISTER TODAY >>

FIGURE 1 and FIGURE 2